June 15, 2008

Hacking the vote

Reliability, more than fraud, bugs voting machines

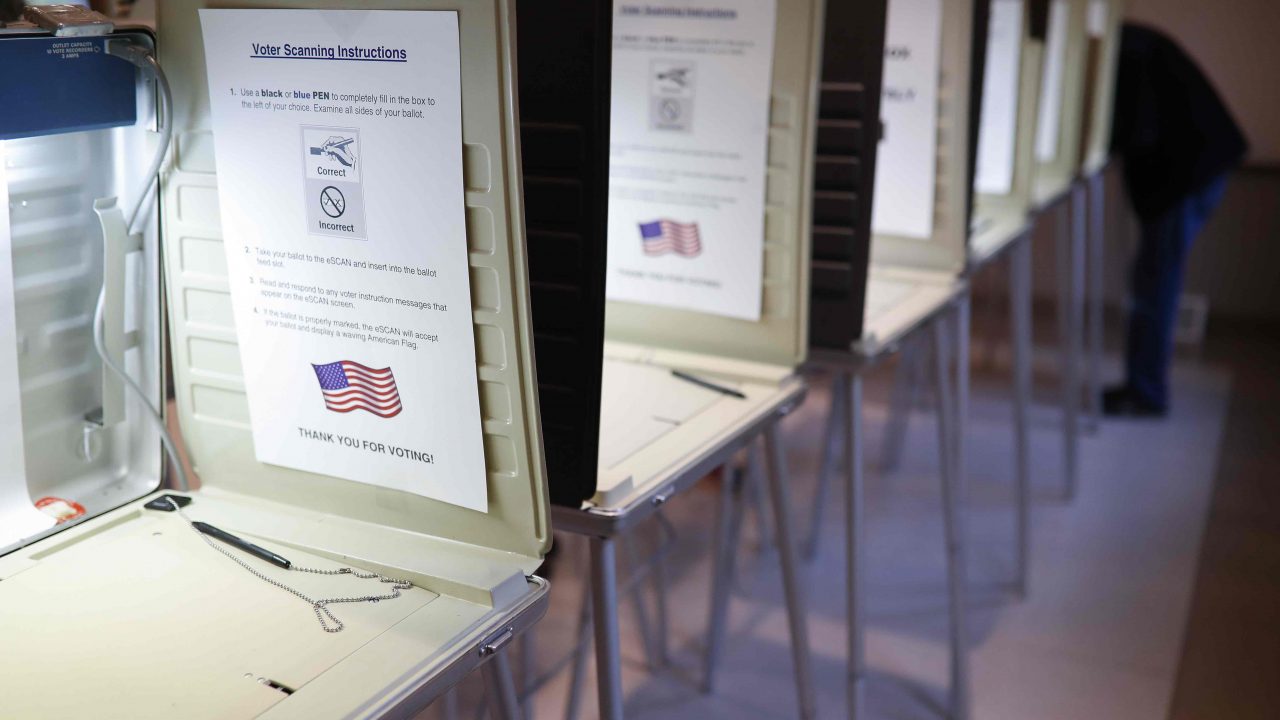

AS AMERICA'S presidential election process stumbles its way towards November, fears are surfacing of yet another Florida- or Ohio-style voting fiasco. In the New Hampshire primary on January 8th, both independent polls before the election and exit polls on the day itself predicted that Barack Obama would soundly defeat Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary. Mrs Clinton's surprising upset cast fresh doubts over the reliability of the computerised machines used to count the vote. Four out of five votes in New Hampshire were tallied by Accuvote machines from Premier Election Solutions, part of the Diebold Corporation. The remainder were counted by hand. Accuvote machines rely on an optical scanner to read paper ballots completed by voters, who use pens or pencils to fill in little ovals next to the candidate of their choice. The machines read the blackened ovals and tally the result. When the results were in, Mr Obama had a four-percentage-point lead on the hand-counted part of the ballot. But Mrs Clinton's three-percentage-point margin on the much bigger machine-counted part made her the overall winner. A manual recount was subsequently abandoned for lack of money. The problem with direct-recording-electronic (DRE) voting systems like Diebold's Accuvote and others from Election Systems and Software (ES&S) and Hart InterCivic is their vulnerability to sloppy installation, poor maintenance, shoddy software, infrequent updates and accidental loss of data. In 2003, an author doing research for a book stumbled across a website on which a copy of Diebold's source code for its voting machines along with manuals and memos from technicians were posted for all to see. Word about the machines' appalling security quickly spread through the blogosphere. A team of computer scientists—three from Johns Hopkins University and one from Rice University—subsequently published a scholarly critique of the Diebold software. They found hundreds of flaws in the source code, ranging from lack of password protection on the main database to bugs that allowed people with a certain type of smart-card to vote as many times as they liked. The software provided no way to verify that a vote had been correctly recorded, and no permanent record was kept. The company claimed that particular software was out of date, and had never actually been used in an election. But the biggest indictment of DRE machines yet has come from Ohio. Recall that Ohio was where election officials purged tens of thousands of eligible voters from the rolls and illegally derailed a recount during the 2004 election that many believe would have given John Kerry the presidency. The 334-page follow-up report, published last month, paints a disturbing picture. The independent researchers found numerous design and maintenance flaws. One machine from ES&S known as the M100 even accepted counterfeit ballots. Premier's AV-TSX allowed unauthenticated users to tamper with its memory. The Hart EMS had audit logs that could be easily erased. On all machines, the root cause of the poor security was the way standard practices for key and password management, security hardware and cryptography had been blindly ignored. Auditing was virtually non-existent. Logs of events happening during an election could be easily forged or erased by those operating the system. In all cases, the software was deemed “fragile” at best. Yet these are the machines that 100m Americans will use to record their vote in the months ahead. The $3.9 billion of federal money allocated to state election boards in 2002 following the Florida fiasco has led to some 40,000 DRE machines being installed across the country. Far from making elections more representative and transparent, the machines seem to have made matters worse. This does not mean electronic voting should be abandoned. After all, ordinary ballot boxes can be stuffed or stolen. Indeed, the vote-counting mess in Florida during the 2000 presidential election—the cause of America's wholesale adoption of electronic voting—was triggered by inadequacies in paper-based balloting. Bruce Schneier, a blogger on security technology, argues that the failure of electronic voting stems from the way technology invariably increases the number of steps in any process—with each step bringing yet more scope for errors. Optical scanners, for instance, have twice as many steps as manual counting, making them at least twice as unreliable. First, the voter reads the ballot paper and fills in the ovals, the optical reader senses the blackened ovals, the scanner passes the vote to a tabulator, the tabulator collects all votes from that machine and then transmits the score to a central totaliser. Each step can have an error of a percentage point or two, giving the system as a whole something like a 5% error. That means one in 20 people using a DRE machine will have his or her vote counted incorrectly. Mr Schneier has two suggestions. First, all DRE machines should have a paper audit trail—so the voter can verify the choice of candidate selected and confirm that the vote was, indeed, recorded. The paper audit also acts as a backup copy in case the machine fails and a recount is required. For added security, the voter wouldn't be allowed to take a copy of the audit home. If they did, unscrupulous individuals might be encouraged to sell their vote. The second recommendation is that the software used on DRE machines should be open to public scrutiny. Interested parties could then review the software, identify bugs and correct them. That alone would do much to increase public confidence in the process. An interesting wrinkle on these suggestions has recently been proposed by Ronald Rivest, a computer scientist at MIT, working with Warren Smith, a mathematician and voting-reform advocate. In their scheme of things, each voter would take home a photocopy of a randomly selected ballot cast by someone else. Meanwhile, the paper ballots would be tallied by optical scanners or hand, and their serial numbers posted on a website along with the voters names. Voters could then check to see whether the serial number of the randomly selected ballot they had taken home had been recorded correctly. A lot of us wouldn't bother to check, but that wouldn't matter. Enough newspapers, political parties, activists and bloggers would. The beauty of the scheme is its low-tech simplicity and transparency. Professor Rivest and Dr Smith have shown mathematically that only 50 votes would need to be checked to prove (with a 95% certainty) whether or not a sample as small as 6% of the vote had been tampered with. If the margin of victory was less than that, imagine the scramble there would be on the web to verify the election. Fear of that would put a stop to the kind of system errors and vote-rigging seen in Florida and Ohio. Better still, it would give citizens the confidence that their vote had been recorded correctly. And you never know, that might even encourage more of us to go out and exercise our democratic privilege. [http://www.economist.com/node/10573225]